Why so many Black people felt seen in Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl performance

From sugarcane fields to reggaeton, fans and music historians alike felt connected to the Black histories behind the halftime show.

From sugarcane fields to reggaeton, fans and music historians alike felt connected to the Black histories behind the halftime show.

As we danced in our living rooms and in the streets to Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl halftime show this past Sunday—to words we may or may not have known—there was a collective feeling among many people, but particularly Black people: we felt seen.

Bad Bunny’s highly anticipated and (contested) halftime show did something that can be incredibly hard to do for any one performance. With just 13 minutes, he packed in lifetimes of history, culture, and ancestral love. In this political climate of anti-diversity and anti-Spanish-speaking fervor, it was an even greater feat. Any one of our parents, cousins, aunts, or uncles could be whisked away by ICE and detained if they “appear” to be Latino or Haitian and have the audacity to be bilingual right now—but Bad Bunny made every ICE agent in the proximity of a television have to hear that Spanish uninterrupted.

As a child, growing up Black and Puerto Rican in the United States could sometimes feel like being doubly invisible. People couldn’t understand my Blackness as being part of Latinidad, or Latinidad outside of what was commercially sold to them.

Bad Bunny’s performance left no part of me behind. My Black Americanness, my Boricua (Puerto Rican) identity, and my American identity were all represented on that stage. The best of our cultures were celebrated, and even the ugliest parts were interrogated with artistic nuance.

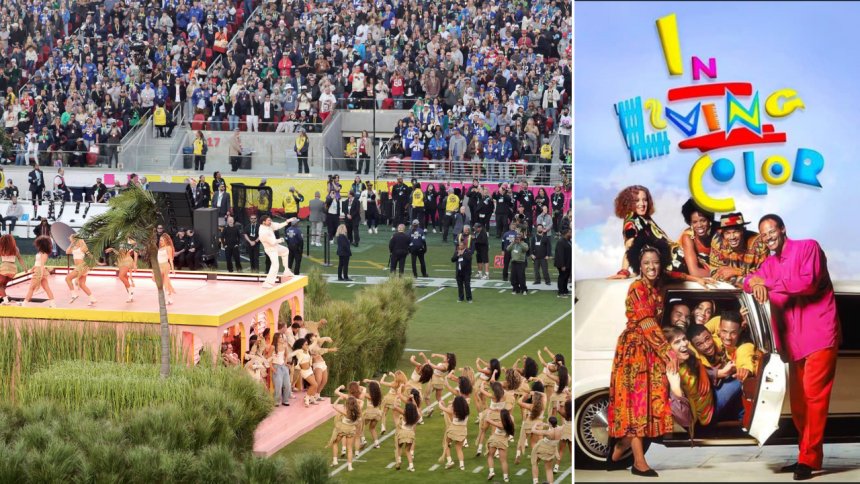

The show started with shots of sugarcane fields—actually shot in the Dominican Republic, on land that existed in the time of the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

“This presentation in so many ways was Black. I mean, from the actual beginning in the sugar cane fields being a nod to the plantation—when have we ever seen something like that on a stage of this magnitude, exemplified with these genres, reggaeton, salsa?” reacted historian and artist Reggaeton Con La Gata in an interview with theGrio. “I was just honestly in shock from second to second and eager to see what was going to happen next.”

These were the sugarcane fields where Spanish colonizers exploited both Indigenous people and Africans—an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 trafficked from the motherland to Puerto Rico alone—representing the origin for so many Black people across the diaspora in the Americas. From the cotton fields of South Carolina to the cane fields of Jamaica, Barbados, and Grenada, and more—we did not ask to come, and yet our labor made countries and empires the wealthy powers they are today.

When did we ever expect to see that story on the Super Bowl stage? Normally dominated by flashing lights, pyrotechnics, and musical stories focused more on the party of it all than the purpose. Yet Bad Bunny found a way to dance to and through it.

The reggaeton art form that catapulted Bad Bunny into fame originated in the Blackest parts of the Caribbean, going back to when Jamaican canal workers came to Panama, sparking a fusion, remixing, and rebirthing of the dancehall reggae genre.

“That boom chick boom that we love so much, that heavy bass, that drum pattern that we hear in reggaeton—that comes from that fish market rhythm that goes into the dembow rhythm. We all know dembow, Shabba Ranks,” Gata explains about the musical elements of the genre.

“It evolved into something that Puerto Ricans added their grains of sand to—what this beach is of reggaeton—by adding their own particular drum patterns inspired by Bomba y Plena, adding their slang, which was more inspired by the New York Rican diaspora,” she continues.

But more than good sounds and beats, reggaeton’s origins in Puerto Rico’s Afro-descendant communities were political. Similar to hip hop in certain eras, it was policed and shunned as not respectable—something Black Americans know well.

“This music was quite literally its first enemy of the state, not just the National Guard who was policing the projects in Puerto Rico,” Gata tells theGrio.

Bad Bunny nodded to these Black musical origins when he shouted out the OGs of reggaeton like Don Omar, telling the Super Bowl audience that “this is the music of the caseríos and projects in Puerto Rico.”

Black millennials who went crazy at the sound of a “Gasolina” sample at the Super Bowl should know that Daddy Yankee literally got it out of the mud.

“Yankee put thirty thousand dollars of his own money into ‘Barrio Fino’ because people wouldn’t invest into that project,” Gata tells theGrio. “And today, Bad Bunny—the world is his oyster. So it’s a beautiful trajectory.”

Bad Bunny didn’t just make us move our hips to modern reggaeton; he also honored the Blackness of bomba, and most prominently Afro–Puerto Rican plena and salsa. The performers we saw in white outfits, holding engraved instruments like maracas, güiro, and panderos, embodied plena—protest music often called a “sung newspaper.”

If you’ve been to a Black American church, just think of the call-and-response a pastor may do with his flock to music. A political, protest, or community message is being shared for the people to move accordingly—and move we did.

When it came to dancers, I could look in the crowd and see bodies of all shades and hair textures—afros, 4C, 3C, any alphabet combination—an accurate reflection of the racial diversity that exists in Puerto Rico, a diversity that exists because of movement across borders. Despite an active history of some politicos trying to whiten the population by encouraging the immigration of Europeans to the island (a policy that feels very similar to reverse browning attempts in the continental U.S. right now), the presence and influence of Black people is undeniable.

“Growing up Black & Puerto Rican, I was always told ‘you don’t look Puerto Rican,’ so I always struggled with that when I was younger, even though my mom (a proud Nuyorican) raised us to be fully aware of our culture,” wrote “Tastemade” host Alex Hill.

“Seeing all the colors & shades of the Caribbean diaspora was beautiful & very, very intentional by Bad Bunny! A proud Boricua!”

Even outside of Afro-Latino communities, Black viewers across the diaspora were among the most vocal in their support for Bad Bunny’s message because of the relatability of erasure and finding joy in the midst of it.

“This makes me want to dive into Puerto Rican history. The tweets aren’t enough—I need to know more,” wrote Threads user Melanie Chelise.

“Sugar plantations in Barbados were especially barbaric. The enslaved had a life expectancy of only seven years if they actually survived the Middle Passage and made it to a sugar plantation,” wrote Threads user KEJ Productions.

“It’s the first thought I had when Bad Bunny opened his set on the sugarcane fields. To see Barbados’ flag waving with all the Caribbean nations at the end… whew. Tears. We feel seen.”

Haiti, often forgotten in conversations about Latin America, also got a shoutout during Bad Bunny’s rundown of countries in North America; that made it all the more special when he pronounced the country “Ayiti,” its proper pronunciation and original name for the “Land of Mountains,” shared with the Dominican Republic.

The collective excitement from people all over the world for Bad Bunny’s show—the highest viewed in Super Bowl history with 135 million viewers—should signal something to the commercial industries that make decisions in both Spanish-speaking and English-speaking worlds.

Not only do Black people see themselves in stories of the Latino diaspora, whether they literally have Latin roots or can simply relate, but they also want to know more.

If Bad Bunny hasn’t forgotten us, neither should they.

“I think now is truly the time to study and to think about the parallels between cultures,” says Gata. “This collectiveness—I think that’s what we should be aiming for. And I think people will be surprised with what they discover.”

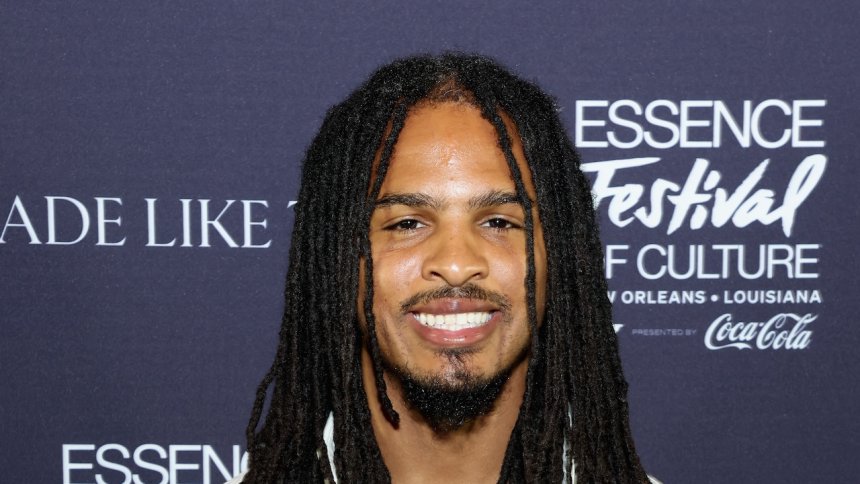

Watch the full interview with Gata of Reggaeton Con La Gata on the video player above.

Share

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0