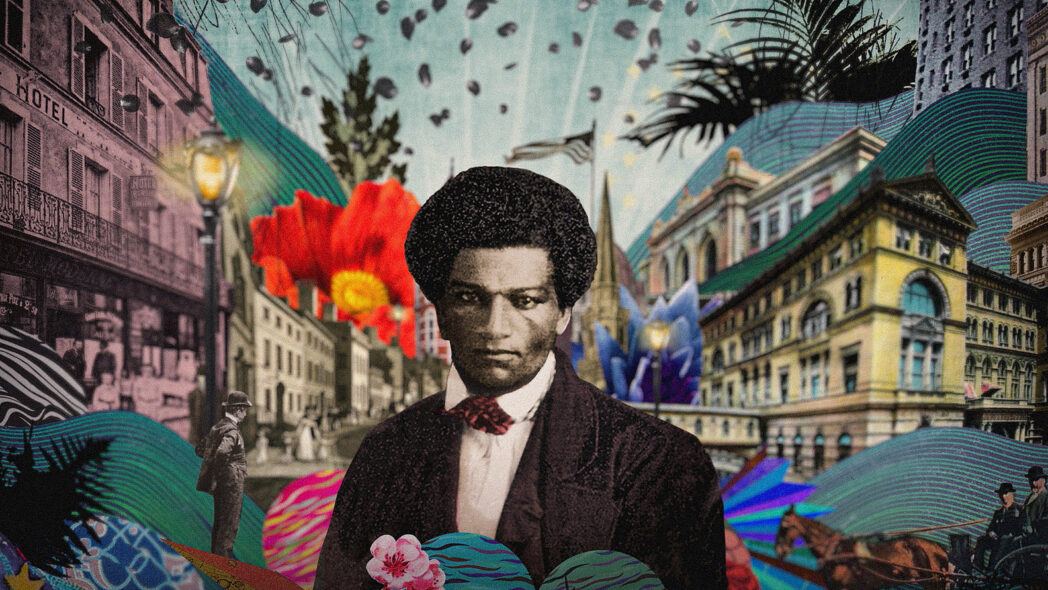

Frederick Douglass: The visionary who redefined freedom and Black liberation

Key takeaways: Among the Black figures who changed history in America, Frederick Douglass emerged as a beacon of defiance and intellect. It’s […]

Key takeaways:

- Frederick Douglass wrote that teaching a man how to read makes him forever unfit for slavery.

- As civil war loomed, he aligned first with the Liberty Party, then threw weight behind the Republicans, certain that dismantling slavery demanded electoral might.

- Postwar, Douglass hounded Congress to ratify the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments.

- His 1852 Fourth of July address before a Rochester crowd tore into the hypocrisy of celebrating liberty while enslaving millions.

Among the Black figures who changed history in America, Frederick Douglass emerged as a beacon of defiance and intellect. It’s hard to tell Black history, or even American history, without telling the story of Frederick Douglass, a man who wove himself into American history through sheer will. Enslaved at birth in 1818, he broke chains of body and mind to emerge as a defining advocate for liberty. His voice, which stolen education sharpened and struggle tempered, reshaped debates over slavery and citizenship, offering ideas that still push against injustice.

Current discussions about race, democracy and equity keep Douglass’s truths urgent. His refusal to accept oppression, paired with a clear-eyed demand for America to live up to its ideals, mirrors modern fights for equity.

From enslavement to freedom: Douglass’s early life

Who was Frederick Douglass? Frederick Douglass, born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, was a Black man who came into the world enslaved in Talbot County, on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, around February 1818. Like many born into bondage, he never pinned down his birthdate. He claimed Valentine’s Day after his mother, Harriet Bailey — who he saw only a handful of times before her death — once whispered “my little valentine” during a rare visit. She died when he was seven. His father’s identity stayed hidden, though whispers linked him to his enslaver, Captain Anthony, overseer and clerk of the wealthy Colonel Lloyd, who owned the large plantation where Douglass grew up.

A man who can read is unfit for slavery

At eight, Douglass went to Baltimore as an enslaved laborer for the Auld family. Sophia Auld started teaching him letters until her husband stopped her, raging that literacy made enslaved people “unmanageable.” The rebuke backfired. Young Frederick bartered bread for reading lessons with white children in the streets and docks, parsing newspapers that shipyards discarded. Words became tools to dissect his condition. He wrote that teaching a man how to read makes him forever unfit for slavery.

His hatred of slavery pushed him to want out. When he tried unsuccessfully to escape slavery, what did Frederick Douglass do? He tried again, his beatings and jailing from his first failed attempt notwithstanding. The first time he tried escaping, he was unsuccessful. Once caught, he faced beatings and jail. His second attempt was a success — he escaped in 1838 at age 20.

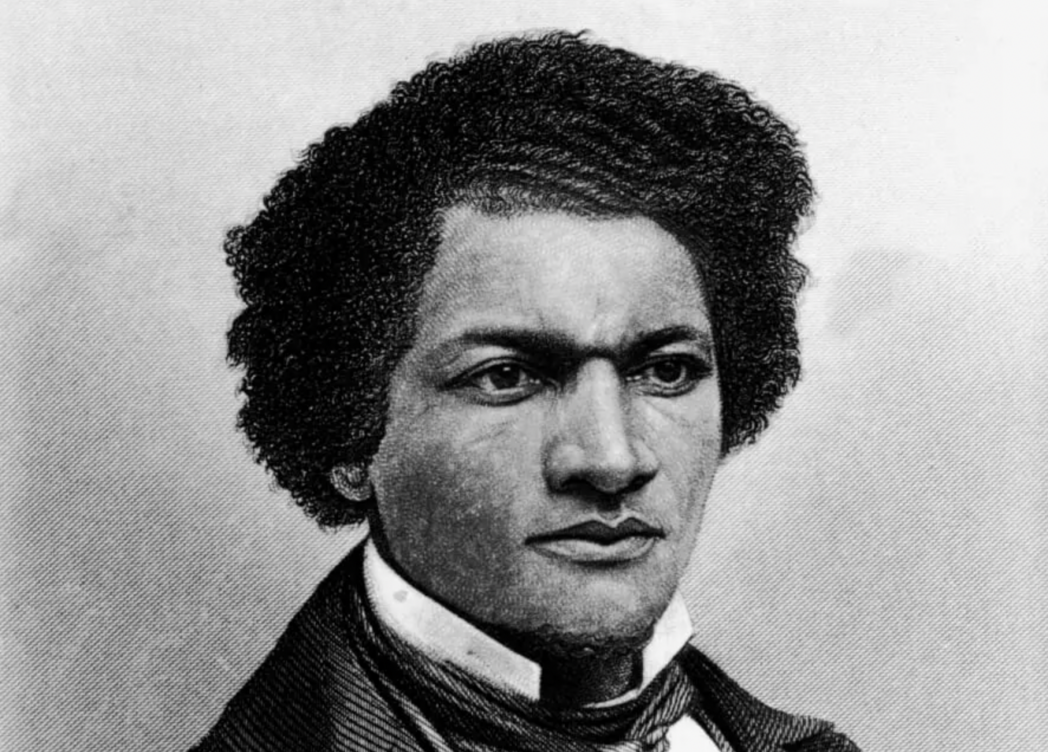

Dressed as a sailor, papers borrowed from a free Black mariner in his pocket, Douglass boarded a train from Baltimore. Twenty-four hours later, he stepped onto New York’s free soil. Anna Murray, a free Black woman he loved, joined him. They married quietly, then settled in Massachusetts, where he chose the surname Douglass — a signal to hunters of fugitives that he’d erased the trail.

Abolitionist and orator: Douglass’s fight against slavery

In New Bedford, Douglass devoured abolitionist writings, finding fire in William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator. A break came in 1841 when he spoke at an anti-slavery gathering in Nantucket. There, Douglass laid bare the visceral truths of enslavement and unmasked the very character of slavery. His words gripped the crowd as the abolitionist movement gained traction. Garrison, touched by the clarity and force of this self-taught thinker, brought Douglass into the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society abolitionist meetings as a speaker.

For 19 months, Douglass crossed the North and sailed to Britain, his voice a blade slicing through myths of Black people’s inferiority. Crowds heard not just pain but precision — arguments so sharp they shredded assumptions. Some refused to believe a man who spoke with such command had ever worn chains, pressing him to relive his enslavement again and again.

Britain in 1845 offered air America withheld, a freedom he’d never known: anonymity from the color line. He wrote that for the first time, he felt like a man, not a color. Supporters there pooled funds to buy his freedom, stripping his former enslaver’s legal claim. Returning home, he carried not just liberty papers but renewed resolve. The global spotlight sharpened his role in the movement, turning him into a symbol of resistance beyond American borders.

Literary legacy: Douglass’s writings and influence

Douglass fought with ink as fiercely as speech. His 1845 “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave” — raw, unsparing — spread like flame. Readers devoured its unvarnished truths, delving deep into the damaging effects of slavery with pages spreading faster than critics could dismiss them. Detractors sneered that no enslaved man could craft such prose until he stood, unshaken, proof alive.

He published two more autobiographies — “My Bondage and My Freedom” (1855) and “Life and Times of Frederick Douglass” (1881, revised 1892), each expanding his story and reflecting his evolving political thought. These books anchor Black literary tradition, their pages proof that a voice once shackled could reshape a nation’s story.

Douglass launched The North Star newspaper in 1847. The abolitionist newspaper pulsed with demands not just against slavery but for women’s rights, schools open to all and justice without exception. Every editorial, every column, turned the press into a lever, prying open minds to make room for freedom.

Political activism and the Reconstruction Era

As civil war loomed, Frederick Douglass abandoned appeals to conscience and seized the levers of political influence. Early ties to William Lloyd Garrison’s pacifist abolitionism frayed as Douglass reframed the Constitution not as a pro-slavery compact but as a blueprint for liberation. He aligned first with the Liberty Party, then threw weight behind the Republicans, certain that dismantling slavery demanded electoral might.

When war erupted, Douglass prodded President Abraham Lincoln toward bolder action. He badgered the president to frame emancipation as the conflict’s beating heart and to arm Black soldiers. Two of his sons wore Union blue with the 54th Massachusetts, while his fiery broadside “Men of Color, To Arms!” drummed thousands into service.

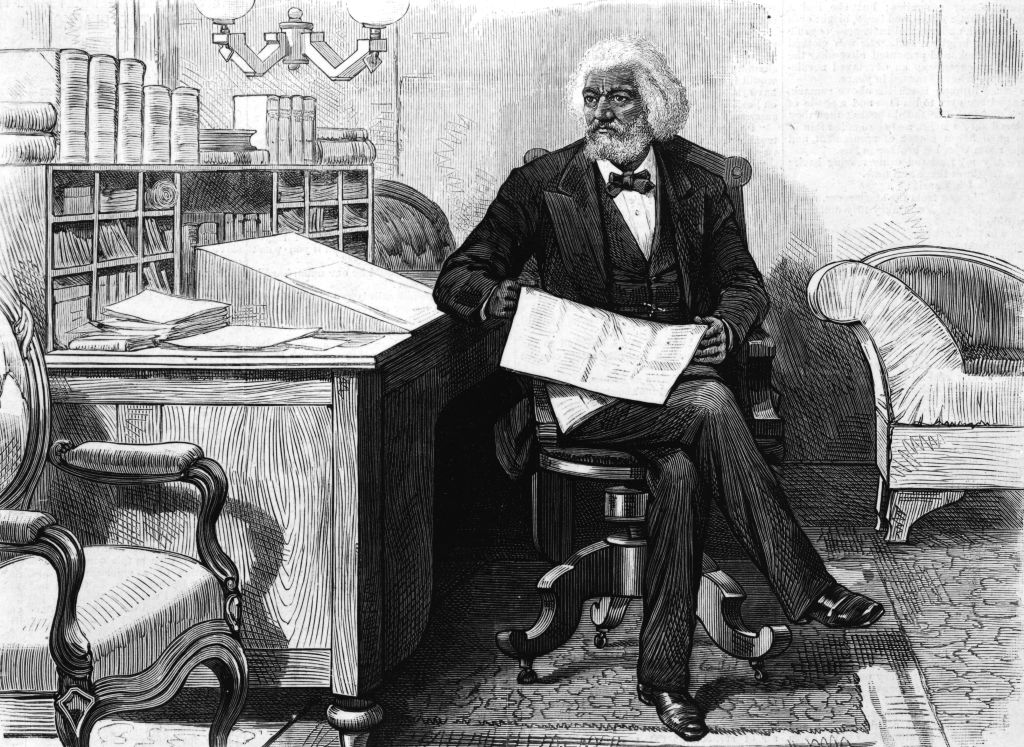

Postwar, Douglass hounded Congress to ratify the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments — edicts erasing chains, codifying citizenship and shielding ballots. The Equal Rights Party tapped him as Victoria Woodhull’s 1872 running mate, though he kept off the stump. Federal roles followed: overseeing D.C.’s courts, property records and later diplomacy in Haiti. No Black American before him had climbed so high in government ranks.

Education and self-determination: Douglass’s core beliefs

Knowledge was the key that unlocked Douglass’s path from bondage to resistance. He grasped early that literacy was not just a skill but a weapon against systems built to silence enslaved people. He argued that it was impossible to keep a man who knew how to read chained. Where slave codes mandated ignorance, he saw enlightenment as rebellion — a truth he carried into freedmen’s schools and newspaper presses.

His speeches on “Self-Made Men” balanced grit against circumstance. Personal drive mattered, he conceded, but so did tearing down barriers. He rejected charity as a substitute for justice, insisting equality meant dismantling the barriers that made “liberty” a hollow word for Black Americans. His refrain “no struggle, no progress” insisted that liberty grew from clashing wills as much as private resolve.

Douglass held America’s founding parchments to the light, demanding they mean what they said. He saw the American Constitution and Declaration of Independence as blueprints for a nation that had yet to exist. His 1852 Fourth of July address before a Rochester crowd tore into the hypocrisy of celebrating liberty while enslaving millions. He asked what the Fourth of July was to the enslaved in America. His answer? A day of mockery, not joy, until freedom stopped excluding those in chains.

Frederick Douglass’s lasting impact and modern relevance

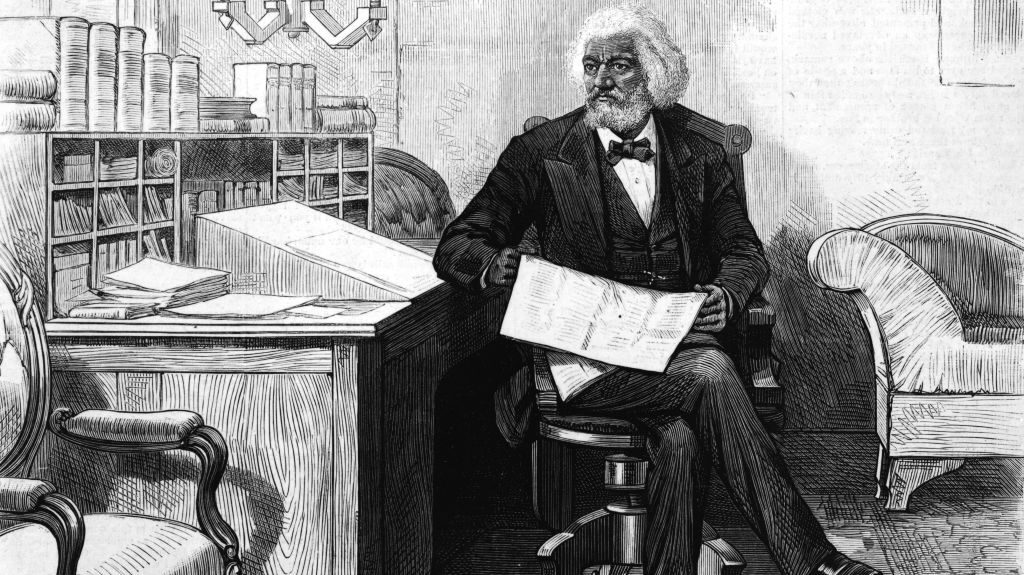

More than a century after Douglass died in 1895, his voice still cuts through the noise. He dissected power’s mechanics, mapped oppression’s reach and demanded full equality — threads woven into today’s fights for racial justice. When Black Lives Matter activists declare that Black lives matter, they voice the same demand Douglass made plain: a society built on stolen breath cannot feign innocence. Long before Instagram, Douglass used photography as a weapon against caricatures, sitting for 160 portraits that dared viewers to deny his humanity. Control your image, he showed, and you start rewriting the rules.

Douglass saw no separation between abolition and women’s rights. In 1888, at a time when many activists treated these causes as rivals, he stood firm, declaring himself a Radical Woman Suffrage Man, framing both struggles as roots of the same tree — a stance modern organizers mirror when linking police reform to housing rights or fair wages.

Frederick Douglass’s accomplishments still resonate with many today. Classrooms still feel his influence. His insistence that literacy fuels liberation shapes fights against unequal schools. Literacy, for Douglass, meant more than parsing sentences. It meant dissecting lies, spotting patterns and asking why. Students in underfunded schools today inherit his battle: education as liberation versus education as compliance.

A legacy that endures

Born enslaved, Douglass forged a life that defied every limit. Today’s generations relish the many facts about Frederick Douglass that make him such an overarching presence in American history. His escape from slavery was only the start — his greater feat was refusing to accept half-freedom. He called out compromises, challenged complacency and fought relentlessly for a democracy that included everyone. Citizenship wasn’t a handout to beg for, but a right to seize.

Douglass was an uncompromising public figure of the 19th century. At 77, he was still pursuing causes of equality and justice for all. He knew progress demands friction and warned that without demand, power concedes nothing — a truth echoing in streets where protesters still chant, “No justice, no peace.”

Douglass’s life argues that freedom isn’t a gift, but a project. And the work he started? Unfinished.

Share

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0