Why the Sydney Sweeney ‘great jeans’ ad sparked backlash — and what it has to do with the history of eugenics

ANALYSIS: The retail company and the “Euphoria” star are receiving criticism that the ad campaign promotes eugenics. Why is that?

ANALYSIS: The retail company and the “Euphoria” star are receiving criticism that the ad campaign promotes eugenics. Why is that?

Everyone, from celebrities like Doja Cat to the White House’s communications team, has reacted to the viral American Eagle “great jeans” campaign starring “Euphoria” actress Sydney Sweeney. The tagline for the ads is “Sydney Sweeney Has Great Jeans” as a play on words, referring to the actor’s looks and her modeling the jeans from the brand.

In one video ad, Sweeney explains that genetic traits such as hair and eye color are passed down from parents to offspring, as the camera pans from her zipping up the American Eagle jeans to her face, revealing her blonde hair and blue eyes. The ad ends with the same play on words, where she says, “My jeans are blue,” with the campaign tagline appearing at the end.

How does an ad campaign with a blonde-haired, blue-eyed celebrity promoting good jeans/genes draw criticism that this marketing originates from eugenics? Some onlookers say critics are reading too much into the campaign. However, the production and execution of such a campaign would have been thoroughly examined and approved by many teams at multiple levels, as explained by TikTok user Matty Pipes in a breakdown. To understand the argument that Sweeney’s ads are more sinister than what is shown on the surface, it’s important to understand the eugenics movement and how it has historically targeted Black people and other marginalized groups.

What Is Eugenics?

Eugenics is the belief system that genetic traits are determinants of human characteristics, and that science can and should be used to ensure only people with desirable genetics can procreate. The movement was first popularized in the United States in 1907 and was accepted as a biological science for decades.

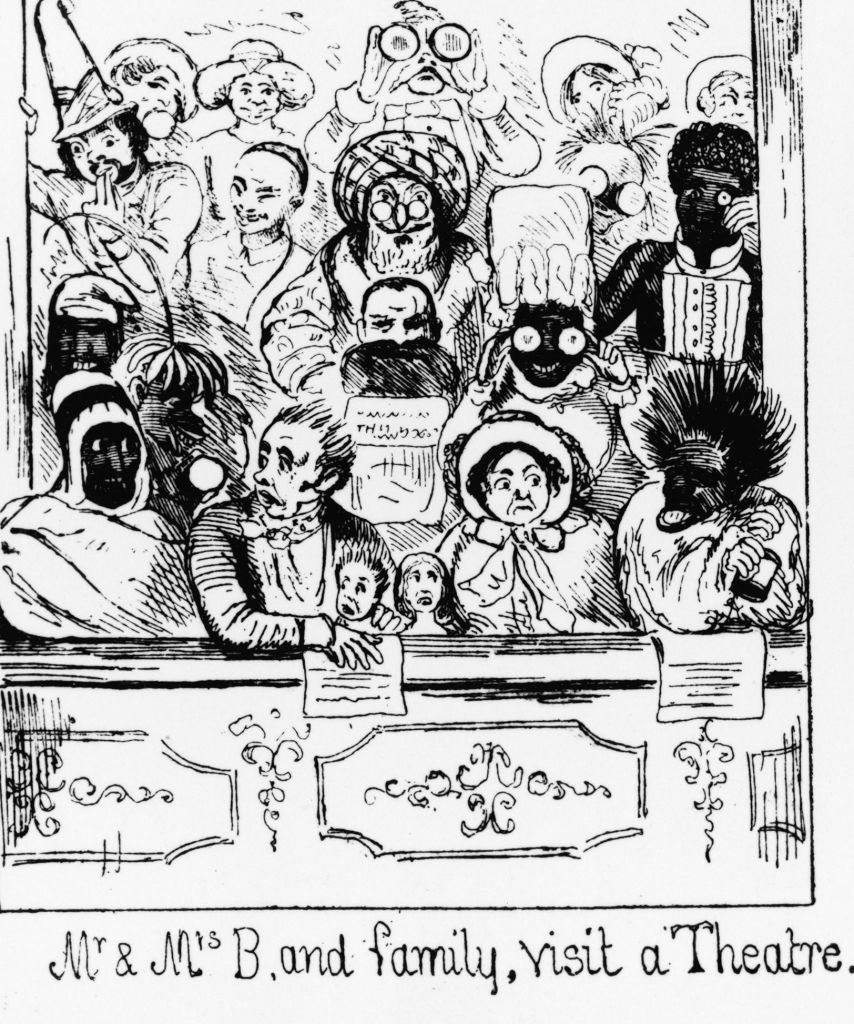

Scientific racism, which uses pseudoscience to argue that white people are superior to nonwhite people, served as a precursor to eugenics theory. The term “eugenics” was created in 1883 by English statistician Francis Galton, a cousin of Charles Darwin. Galton used fake science to determine that Black people were inferior to white people, such as comparing heights, fingerprint patterns, and facial features. He argued in his widely criticized book, “Hereditary Genius,” that governments should be working to build a society of “geniuses” by preventing people of lower intellectual ability from procreating and making sure people with higher intellectual ability continue to procreate.

One of the leaders of the American eugenics movement, Harry Hamilton Laughlin, described in his book “Eugenics in America” that five factors — heredity, mate selection, differential fecundity, differential survival, and differential migration — could be used to “predict what is happening to the human race.” Laughlin zoned in on mate selection (deciding who was fit or unfit to have children) as a main focus, becoming a champion for legal forced sterilization in this country. From 1907 onward, 31 states would pass involuntary sterilization laws.

Giving Birth, Sterilization, and “Good Genes”

Forced sterilization laws in the US permitted the sterilization of disabled and poor people of all races, but that’s not to say that race wasn’t a major component of eugenics. The bill Laughlin helped produce, was used as a framework for the “racial hygiene” law enacted in Nazi Germany in 1934. The Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler upheld the “Nordic Race” as Germany’s eugenic standard. Racially acceptable couples who were considered fit to have children had traits such as, among other things, blond hair and blue eyes.

In the US, women of color were disproportionately affected by the eugenics practice of forced sterilization. Black women in the South, like the civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer, were exploited by the surgery, which was so widespread that it was nicknamed the “Mississippi Appandectomy.” The US territory of Puerto Rico was also used as a site for forced sterilization, known by many as “la operación.” Almost one-third of Puerto Rican women were coerced into testing for the development of the modern birth control pill from 1937 into the 1970s. The island had the highest sterilization rate in the world. In 1970, Native American women were legally subjected to the practice, sterilizing an estimated 25 percent of women of childbearing age over six years.

Even though the movement was popularized in the first half of the 20th century, evidence of eugenics practices in the United States has been documented through the end of the century and well into the 2000s. Some form of forced sterilization is still legal in 31 states, according to the National Women’s Law Center. The 150 state-sanctioned sterilizations in California prisons between 2006 and 2010, mainly affecting Black and Latina women, are a harrowing example of these modern-day cases.

What Makes “Good” Genes?

While it’s a common phrase to say someone has “good genes,” what complicates the American Eagle ad campaign is its assertion of what those good genes are. Is the insinuation that Sweeney has good genes because she’s blonde, white, and pretty? What does that mean in a diverse nation with a history of oppressing people who don’t look like her? And where many were punished for not having good enough genes?

Sweeney’s ads may also be especially ill-timed in the era of a Donald Trump presidency, where racism and white supremacy are key components of the administration’s platform. In a political climate where the Department of Homeland Security head Kristi Noem is nicknamed “ICE Barbie” for using deportations as a backdrop for flattering photo ops, Americans may be becoming more conscious of the ways that beauty is used to downplay the seriousness of our political state.

Nhari Djan is a New York-based reporter covering weekend news stories at theGrio. She has previously worked as a business reporter at Observer and Business Insider, and has also written and worked for publications like Health, Bustle, Elite Daily and PopSugar.

Share

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0