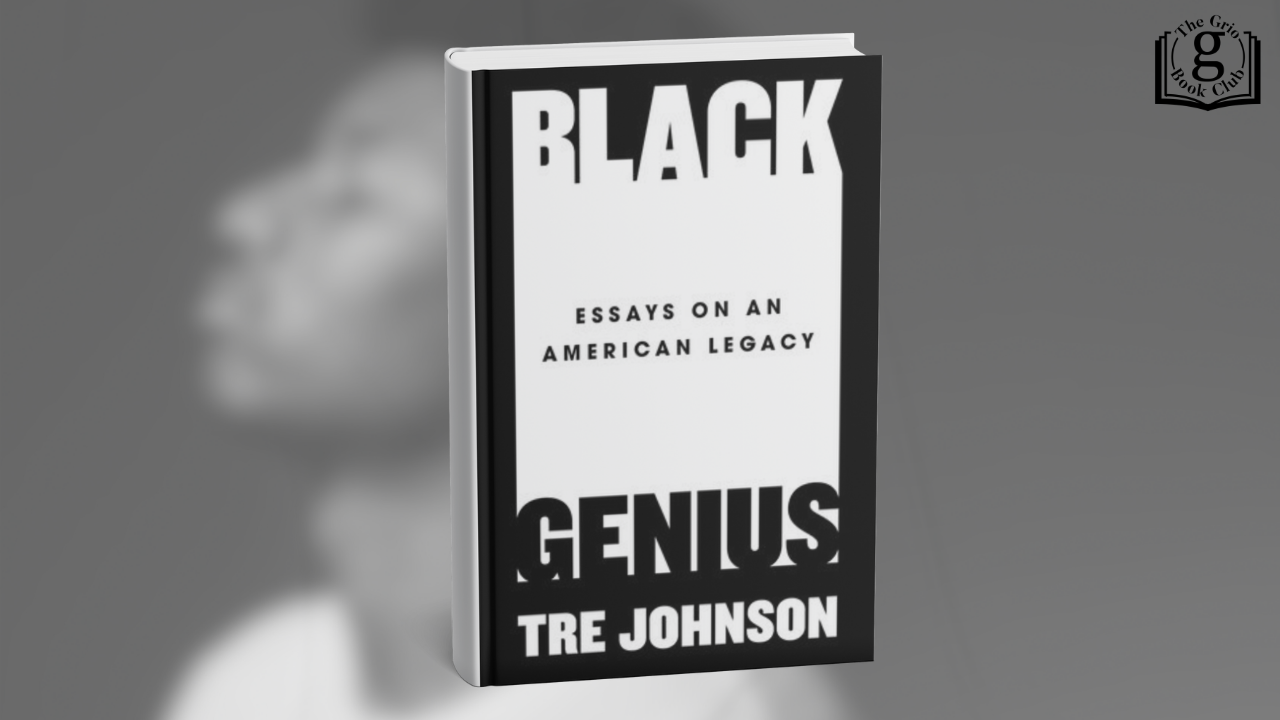

What schools miss about Black genius — an exclusive excerpt from Tre Johnson’s new book

Grio Book Club Excerpt: In his new book “Black Genius: Essays on an American Legacy,” Tre Johnson shares the story

Grio Book Club Excerpt: In his new book “Black Genius: Essays on an American Legacy,” Tre Johnson shares the story of his Uncle Alan, who coined “streemal education” to describe the brilliance it takes for Black kids to thrive between “street” and “formal” worlds.

Editor’s note: The following is an excerpt from Chapter 2 of Tre Johnson’s book Black Genius. It has been lightly edited for clarity.

Education is supposed to be the door to a better life and set of opportunities, but too often the American education system smothers and smooths over Black genius. And in the process, our education system crushes and overlooks those of us who manage to use a series of academic, cultural and interpersonal brilliance to navigate the typical school settings and still thrive against the odds. Most of the time, schools, educators and fam‑ ilies consider kids to be academic geniuses based on straight A’s, high SAT scores and getting into elite high schools, colleges and universities. And those are genius markers, but there’s also the ingenuity of genius that flies under the radar and doesn’t look as obvious. It’s a Black genius that has to understand tricky aca‑ demic, social and cultural terrain in a bunch of different circum‑ stances and basically create a DIY life curriculum to make it through.

I want this Black genius celebrated as well; the kind of Black students who find a way through a complex series of relationship negotiation, academic risk‑taking, cultural creation and imagination. In my family, one of the geniuses, my uncle Alan, tried to define this sort of genius by telling people how he made it from deep Trenton to the University of Pennsylvania. As an educator, my years working in nonprofits and at schools forced me to reconcile how often I was being coaxed to value a limited definition of genius, and how that work sometimes made me lose my sense of authenticity, integrity and awareness of the world around me. For me, the beginning of those epiphanies came on the biggest stage at the worst possible time.

My uncle Alan went through a social‑academic baptism by fire. He grew up the youngest of three siblings in 1960s Trenton and was the last child in my grandparents’ house, my dad Wayne and my aunt Debbie both having left while he was still growing up. As a Black kid growing up in deep Trenton the closest school was Stokes Elementary. Not that he was there all that long; his boredom and acting out became proof that my uncle often out‑paced everyone around him. Eventually, though, he convinced Nana to let him transfer to Princeton Day School, the nearby posh private school that offered him a scholarship. At Princeton Day School, he sat next to kids who came from the Gallup, Pack‑ ard and Johnson (of Johnson & Johnson) families. And while that scholarship got him in, it didn’t make him an insider at PDS; at first, the school placed him academically at the bottom of their classes. His second week there, a white boy called him “n*gger” to his face.

Alan spent six years—sixth grade to twelfth grade—moving back and forth between two worlds: my grandparents’ brick row‑ home in Trenton and the sprawling campus of PDS. Looking back on that time nowadays, he tells me how he started realizing that he was “never quite fitting in either one” anymore; when he went to birthday parties at their mansion houses, his classmates talked about going to Aspen and Vail for spring breaks. Even though he tried to hang, the reality was that he stuck out in all kinds of ways; they all dressed in bespoke suits and fancy dresses while he showed up in whatever leisure suits Nana felt they could afford. And while they all blended in seamlessly with each other at those parties, he would sometimes get confused for the staff by some of his classmates’ family members.

You’d think that being back home in Trenton should’ve been easier, but he started finding that people on the block saw him as some kind of snooty, smartass (to be fair, he is a smartass) brother too good to relate to anymore. Still, the mixture of social and academic settings and conversations must’ve been heady for a Trenton kid feeling more out of place wherever he went. In 1968, when downtown Tren‑ ton was full MLK‑assassination riots and razing, he was a fourth grader at Stokes still, and two years later he’d be at PDS, where the kids there probably looked at him like a looter.

The other thing that happened, though, was that swinging between Princeton and Trenton really opened his eyes to how lopsided and unfair things were depending on whether you were Black and poor or white and not poor. And that also meant that he’d have to quickly, and largely on his own, figure out how to do well in school and keep the peace at school (you can’t body‑slam in return every kid who’s going to call you “n*gger” and not eventually end up back at Stokes) as well as when he was back home in the hood…

When he graduated from PDS in 1977 at the top of his class, he turned down an early admission to Princeton University to go to the University of Pennsylvania instead after seeing the Penn Relays on a trip to Philly. By then, the cultural whiplash between PDS and Trenton had given him a lot to think about, and only in the last couple of years did I come to understand what it was like for him… And thinking about what it took to both succeed and survive, he turned it into a college senior paper where he put a name to what he had discovered. He called it “streemal educa‑ tion” ( formal and street ); a combination of what he learned growing up in Black Trenton and the white elite spaces like PDS and UPenn.

And while it might sound like code‑switching, Alan saw streemal differently. Streemal is about melding street education and formal education into an awareness that “opens your eyes to the many inconsistencies of life and makes you scary to a lot of White folks.” I really think what he’s talking about is an earlier coinage of something similar to being woke, and all that really made my uncle was an unsigned rapper. He didn’t have the beats or rhymes, but he knew the life…

Tre Johnson was born in Trenton, NJ and now finds himself in Philadelphia, where he writes with a focus on race, culture and politics. His work has appeared in The Washington Post, Rolling Stone, Vox, The New York Times, Slate, Vanity Fair, The Grio, and other outlets. He has appeared to provide media commentary on CNN Tonight with Don Lemon; CBS Morning Show; PBS NewsHour, NPR’s Morning Edition, and other programs. In addition to writing, Tre is a career educator, working both inside and outside the classroom as a teacher and leader.

Share

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0