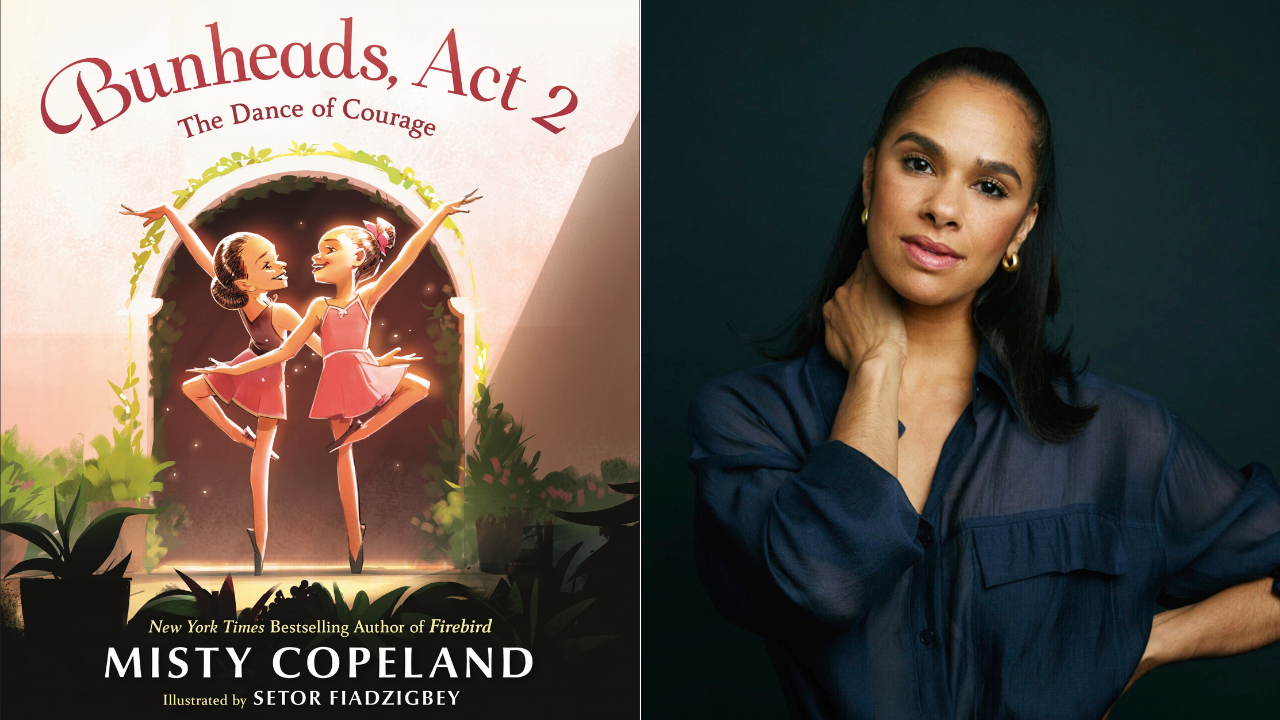

Priced Out Of The Mecca: The Emotional Cost Of Belonging At A Black University In A White City

Source: The Washington Post / Getty On a bright fall morning, Georgia Avenue looks like a city in transition. Coffee shops with sleek glass facades spill onto sidewalks once lined with soul food diners and record stores. Strollers glide past the storefronts, pushed by new residents who, only a decade ago, might have thought twice [...]

On a bright fall morning, Georgia Avenue looks like a city in transition. Coffee shops with sleek glass facades spill onto sidewalks once lined with soul food diners and record stores. Strollers glide past the storefronts, pushed by new residents who, only a decade ago, might have thought twice about moving into the area. And just across the street, Howard University students, most of them young and Black, are running to class, juggling backpacks, SmarTrip cards, and long commutes.

“It feels like we’re not supposed to be here, even though this was designed for us,” says Madison Nicome, a junior studying marketing at Howard. “I’ll be walking to class, and I’ll see a group of white people walking up campus or down Georgia Ave, and it feels… off. Like they’re intruding. But then you realize, no, they’re not intruding. They’re just here. They’ve moved in. And somehow, we’re the ones who feel out of place.”

This is the paradox of Howard University today, A historically Black university, world-renowned for its cultural and political influence, now sits at the epicenter of D.C.’s gentrification. Students are watching their campus neighborhood transform around them, often without them. And many can’t even afford to live near it.

Since its founding after Emancipation, Howard has symbolized safety, pride, and intellectual freedom for generations. But lately, it feels like the ground beneath that legacy is shifting. What’s happening around this campus is bigger than rent spikes or new apartment buildings. It’s a collision between Black educational space and urban displacement, between a community built to protect us and a city that’s slowly pushing us out.

The story of gentrification here isn’t just about housing costs. It’s also about culture, belonging, and identity. Rising rents, luxury developments, and a widening racial wealth gap are changing what it means to be a Howard student and how it feels to walk to class and feel like a visitor in your own history. Students are paying premium tuition to study at a university surrounded by a city that’s becoming less and less accessible to the very people who made it what it is.

This is part of a bigger American contradiction: Black excellence celebrated in headlines and hashtags, but displaced in real life. What’s happening around Howard mirrors what’s happening across the country, and the people caught in the middle are students just trying to learn, work, and exist in peace.

Too Expensive to Stay

In 2024, the average rent for a one-bedroom apartment within walking distance of Howard was nearly $2,200 a month, according to Zillow data. For students who came to Howard without family wealth or steady financial support, that price tag is impossible.

“I live in Hyattsville now, almost an hour away by metro,” says Zhane Sligh, a junior nursing student. “I used to think college was just me rolling out of bed and walking to class. But that’s not true on this campus. It’s two trains, sometimes a bus, and if I’m late or miss a connection, that’s my whole day thrown off.”

Students who can’t secure on-campus housing are increasingly pushed to the outer edges of the DMV to places like Prince George’s County, Silver Spring, and Hyattsville. The commute costs add up. A Metro round-trip averages $6–10 a day. Some students resort to Uber when running late, which can quickly reach $20–$30 for a single ride.

“That’s money we don’t have,” Sligh adds. “Between tuition, food, rent, bills, every dollar is stretched. And the longer you’re here, the further you get pushed away from campus.”

According to the D.C. Policy Center, rent prices in neighborhoods surrounding Howard have increased by more than 35% since 2015. In that same period, the median Black household income in the District fell by roughly 7% when adjusted for inflation. These trends mean that even as Howard expands its academic footprint, the communities that once sustained its culture are being priced out.

Howard is not alone. HBCUs across the country, from Spelman in Atlanta to Morgan State in Baltimore, are wrestling with housing crises and skyrocketing local rents. But at Howard, located in the heart of the nation’s capital, the visibility of gentrification makes the issue especially raw.

Walking Through a Changing Neighborhood

For many students, the daily walk to campus is tinged with unease. The surrounding increasingly white neighborhood feels like contested ground.

“Walking around as a Black man, you feel the shift,” says Aaron Elliot, a senior majoring in International Business. “When I came in as a freshman, Georgia Ave felt like it was ours with Black-owned shops, people who looked like us, culture that reflected us. Now, you’ll be walking, and you see white residents jogging, walking their dogs, carrying yoga mats. It’s like, when did this become their space? We’re the ones who feel out of place now.”

The feeling is less about individual white residents and more about systemic change. Gentrification doesn’t just bring new coffee shops; it brings rising rents, evictions, and cultural erasure. What was once an affordable hub for Black families and students is now priced out of reach.

“It’s like they don’t even see us,” Elliot adds. “They walk past us on Georgia Ave, headphones in, like we’re background noise in their neighborhood.”

D.C.’s Black population has fallen from 71% in 1970 to less than 45% today. The neighborhoods surrounding Howard — Shaw, Bloomingdale, and LeDroit Park — have seen some of the most dramatic demographic shifts in the city. Once known as “Chocolate City,” Washington now mirrors a national pattern of historically Black spaces being redeveloped in ways that exclude the very people who built them.

The Costs of Staying in School

Howard tuition has risen steadily in the last decade, topping around $64,000 a year for undergraduates. Add in rising food prices, housing instability, and the hidden tax of commuting, and the financial pressure becomes suffocating.

“You can’t separate tuition from housing,” says Dr. Silas, a Howard alum and professor in Howard University’s School of Business Cybersecurity department. “What’s happening is that students are being priced out of the very community their university helped sustain. The promise of education is tied to place, and when students are pushed further and further away, it undermines that experience.”

Some students double up in crowded apartments, sharing one-bedroom units among three or four people to make rent. Others move home with family and take long commutes back in. For those without safety, the stress is immense.

“Every extra hour I spend on the train is an hour I’m not studying or resting,” says Silas. “It’s not even just about distance anymore.”

Howard officials have acknowledged the strain but say the university is exploring options. In a statement, a spokesperson said Howard has invested in new residence halls and partnerships with local developers to increase access to student housing as part of a broader $500 million initiative launched in 2023. The plan aims to modernize existing dorms and expand capacity for students displaced by D.C.’s rising housing costs. But students and advocates argue that these efforts still fall short of addressing the scale of the city’s affordability crisis.

“This is not just about housing,” Dr. Silas explains. “It’s about erasure. Students are experiencing firsthand what generations of Black families have faced: being priced out of the very communities they built. And when you’re a student, already carrying debt, the displacement hits harder.”

What Comes Next?

Some students are calling for stronger university intervention — more affordable dorms or partnerships with nearby landlords. Others argue the city itself needs to address systemic affordability issues through rent stabilization and expanded housing vouchers.

But for many, the reality is immediate and personal.

“I graduate this year,” Elliot says. “I just keep thinking: what’s Howard gonna feel like for the next class of students?”

Sligh echoes the sentiment: “I’m proud to be here. I’m from the DMV area, but every time I walk past a new condo or see another white family pushing a stroller, it feels like we’re disappearing. Like Howard’s here, but the Howard experience is slipping away.”

For Howard students, the fight is not just for a degree. It’s for visibility in a city that often pretends not to see them. It’s for space in a neighborhood built by and for them. It’s for the right to belong right where they’ve always been, even as the city around them tries to forget.

DuWayne Portis is a junior journalism major at Howard University.

SEE ALSO:

‘Empathy Is Hard To Find In The Big House.’ A Howard Student Fears SNAP Cuts Ahead Of The Holidays

Share

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0