10 undisputable facts about slavery in the U.S.

Here are ten shocking facts about slavery and American descendants of chattel slavery who survived the unthinkable in the United

Here are ten shocking facts about slavery and American descendants of chattel slavery who survived the unthinkable in the United States.

Slavery is often taught as a straightforward chapter in American history: it began, it was brutal, it ended with the Civil War, and the nation moved on. But the truth is far more complex, global, and enduring than most of us ever learned in school. The transatlantic slave trade spanned centuries, reshaped continents, and created a legacy that still shapes life today.

At a time when history is being rewritten by forces who want to soften or whitewash the ugliness of America’s original sin, here are ten undisputable facts about how chattel slavery is part of this nation’s story.

1. The sheer scale of the Transatlantic Slave Trade was huge.

Between the early 1500s and the late 1800s, an estimated 12.5 million Africans were forced onto ships bound for the Americas. Of those, only about 10.7 million survived the horrific journey across the Atlantic known as the Middle Passage (Gilder Lehrman Institute).

Here’s what shocks most people: only about 5% of enslaved Africans ended up in what is now the United States. The vast majority were transported to Brazil and the Caribbean (PBS).

According to firstblacks.org, the Spanish brought enslaved Africans to the island of Hispaniola, now known as the Dominican Republic and Haiti, in the late 1490s.

Slavery in the U.S. was distinct in that it was race-based and legally encoded into every aspect of American life. Slaves were treated like cattle and property, down to their flesh burnt and branded.

2. Slavery’s legal end came shockingly late and persisted after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed.

Although the Emancipation Proclamation was issued in 1863, it only applied to enslaved people in Confederate states under rebellion—and it couldn’t be enforced in areas still under Confederate control. Slavery legally persisted in Union border states like Kentucky and Delaware until the ratification of the 13th Amendment in December 1865.

This is why we celebrate Juneteenth—June 19, 1865—marking the day when enslaved people in Galveston, Texas, finally learned of their freedom, more than two years after the Proclamation. Juneteenth reminds us that slavery’s legal end came shockingly late and that freedom was staggered and uneven, resisted by those invested in maintaining white supremacy.

After slavery, Jim Crow and segregation laws took its place.

That segregation systems existed within the lifetimes of people walking around today, and de facto segregation still exists today.

3. Some companies and universities still around today profited from slavery.

When we talk about slavery, we rarely connect it to corporations or institutions that continue to exist. But the links are there. For example, Lloyd’s of London, one of the world’s most famous insurance markets, was built in part on insuring slave ships. The British brewing company Greene King also profited directly from slavery, and both have since pledged reparations (Axios).

In the United States, elite universities like Harvard, Yale, and Georgetown have acknowledged that they were built on slavery-related wealth, whether through donations from slaveholders or by directly enslaving people on campus (Investopedia).

Several major American companies can trace part of their origins to slavery and the slave economy. Brooks Brothers, for example, sold “slave livery” garments in the 19th century, producing rough uniforms designed for enslaved people on plantations. Insurance giants like Aetna and New York Life once wrote policies that treated enslaved people as property, compensating enslavers if those they held in bondage died.

Banks including JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, and Wachovia (now part of Wells Fargo) accepted enslaved people as loan collateral and sometimes seized them outright when debts weren’t paid. Lehman Brothers began as a cotton brokerage in Alabama, profiting from slave-grown cotton, while early railroads like those that became CSXrelied directly on enslaved labor to build tracks and infrastructure. These ties reveal how deeply slavery was woven into America’s financial and corporate foundations, leaving legacies that persist in wealth gaps and systemic inequities today.

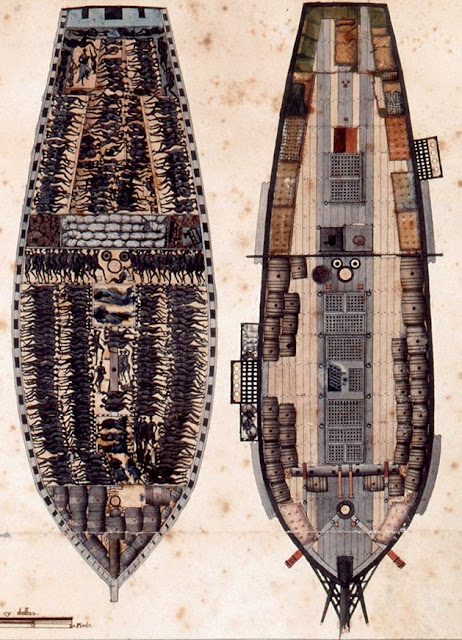

4. The brutality of the Middle Passage was unimaginable.

The Middle Passage—the sea route enslaved Africans endured across the Atlantic—was one of the most horrifying aspects of the slave trade.

Captives were chained together, packed into suffocating spaces below deck, and given little food or water. Disease, suffocation, and abuse were rampant. Many were forced to lie for weeks in their own urine, blood, and feces, creating unbearable stench and conditions that spread deadly infections. Women were especially vulnerable to sexual violence at the hands of crew members.

Some captives resisted by jumping overboard, choosing death over enslavement. Others starved themselves in protest, only to be force-fed through brutal methods. Mortality rates ranged from 15% to 25%, meaning millions of people died before even reaching shore (Britannica).

The survivors carried physical and psychological trauma that would shape their families for generations.

5. Enslaved people built iconic landmarks and entire economies for the U.S.

Library of Congress

Slavery wasn’t just about fields of cotton and tobacco. Enslaved people literally built parts of America. The U.S. Capitol, the White House, and many historic buildings in Washington D.C. were constructed with enslaved labor (White House Historical Association).

Cities like New Orleans, Charleston, and New York also relied heavily on enslaved labor, not just in agriculture but in urban development. Meanwhile, enslaved workers fueled the global economy with sugar, coffee, cotton, and tobacco—commodities that transformed Europe and the Americas.

By the mid-19th century, cotton alone accounted for more than half of all U.S. exports, linking the forced labor of Black people directly to the rise of Wall Street banks, shipping companies, and insurance firms that financed and profited from slavery.

6. Slavery wasn’t just a “Southern Problem.”

While the South is most often associated with slavery, the North was far from innocent. New York, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts all had enslaved populations in the 17th and 18th centuries. Rhode Island alone controlled a majority of the North American slave trade, sending hundreds of voyages to Africa. Enslaved Africans worked in Northern households, farms, and ports, laying the foundations of cities like Boston and New York. Northern merchants financed slave voyages, insured slave ships, and processed goods like sugar and cotton produced by enslaved labor (Hudson Valley Slavery Archive).

Even after formal abolition in the North, Northern businesses profited immensely from the slave economy. Banks in New York and Philadelphia issued loans backed by enslaved people as collateral, and textile mills in Massachusettsturned Southern slave-grown cotton into finished cloth for the global market. Wall Street firms and insurers built fortunes underwriting the slave trade. In short: slavery was a national enterprise.

7. Enslaved Black people were skilled innovators, even while oppressed.

It’s easy to reduce enslaved people to agricultural laborers in historical accounts, but that erases their brilliance and skills. Many were highly trained artisans—blacksmiths, carpenters, potters, weavers, woodworkers—whose craftsmanship shaped the economy and infrastructure of early America (Atlanta History Center).

African traditions blended with American life in food, music, craftsmanship, and agriculture. Much of the rice knowledge that made Southern plantations profitable came directly from enslaved Africans from the “Rice Coast” of West Africa, where rice had been cultivated for centuries (Smithsonian Magazine). The same was true of indigo, which became one of the most lucrative cash crops in colonial South Carolina and Georgia. Enslaved Africans provided not only the labor but also the technical knowledge of how to cultivate and process indigo into dye, helping turn it into a cornerstone of the colonial economy (South Carolina Encyclopedia).

These contributions—whether in agriculture, building trades, or cultural traditions—show that enslaved people were not just laborers, but bearers of knowledge, creativity, and innovation. Their forced exploitation built much of America’s early prosperity while leaving cultural imprints still central to U.S. identity today.

8. The “Happy Slave” narrative is propaganda. Black people were treated like animals.

Slaveholders often promoted the myth that enslaved people were “happy” and well cared for. This wasn’t just ignorance—it was deliberate propaganda to justify slavery. In reality, the system was built on extreme violence and dehumanization. Enslaved men and women were routinely raped by enslavers, with their children sold away for profit, tearing families apart.

Black women’s bodies were exploited in medical experiments, most notoriously by J. Marion Sims, the so-called “father of gynecology,” who conducted surgeries on enslaved women without anesthesia. Black children were subjected to grotesque cruelties, including being used as alligator bait, a chilling reminder of how they were viewed as disposable property. Even newborn babies were ripped from their mothers’ arms and sold on auction blocks.

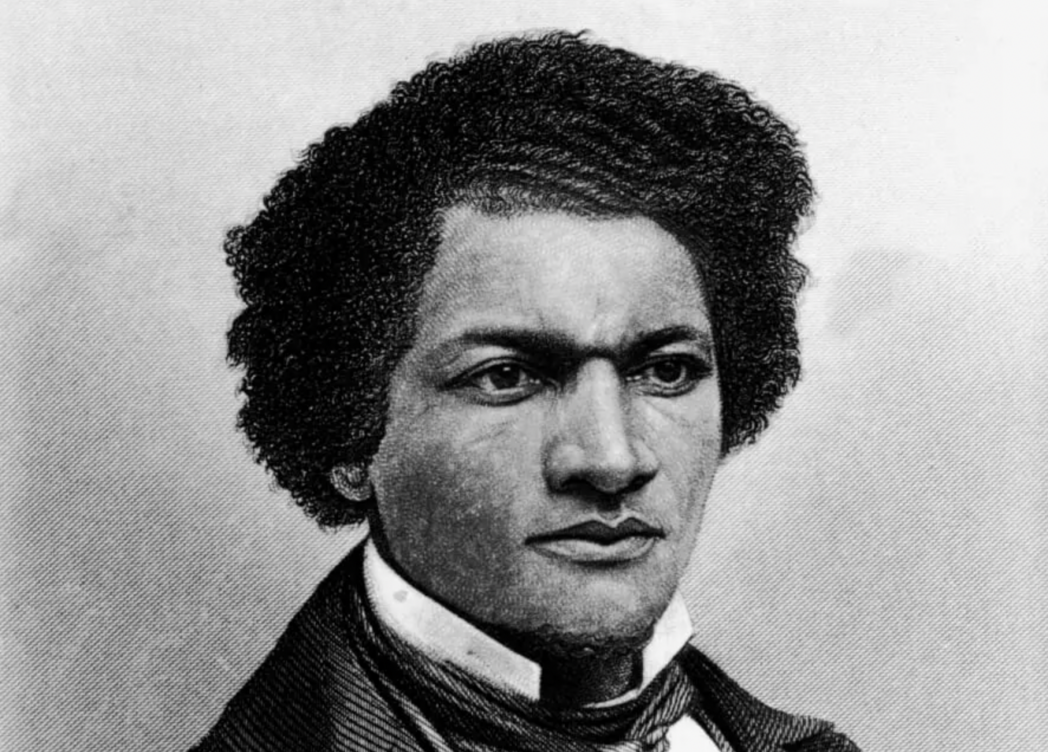

Nevertheless, enslaved people resisted constantly. Some escaped, others sabotaged tools or crops, and many preserved African traditions—through language, religion, music, and storytelling—as quiet acts of defiance. Figures like Frederick Douglass famously dismantled the “happy slave” myth, exposing it as a cruel lie.

9. Enslaved people were the nation’s largest financial asset.

On the eve of the Civil War, the value of enslaved people in the U.S. was estimated at around $3 billion in 1860 dollars—the single largest financial asset in the country, exceeding the combined value of all railroads, factories, and banks (Time). Put another way: enslaved people were the American economy. This fact underscores why so many wealthy elites fought so hard to preserve slavery—it was about money and power as much as ideology.

And even after emancipation, that wealth imbalance was reinforced. In some places, governments paid reparations not to the formerly enslaved, but to their enslavers. For example, in Washington, D.C., the federal government compensated slaveholders nearly $1 million for the loss of “their property” after slavery was abolished there in 1862 (Smithsonian Magazine). Freed Black people received nothing—forced to start from scratch in a society built on their stolen labor.

10. The legacy of slavery still shapes America today.

The story of slavery didn’t end with emancipation. Instead, it evolved into systems like convict leasing, Jim Crow segregation, redlining, and mass incarceration.

Today, the racial wealth gap, disproportionate incarceration of Black Americans, and systemic inequities are direct descendants of slavery’s institutional framework (TIME). As scholars and activists have said: slavery is not the past—it’s the foundation of the present from which Black people have still managed to survive and thrive in spite of it. It’s impact must never be forgotten or diminished.

Share

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0